Living Memories & Dead Media

Every time I look at my bookshelf, or maybe not every time but more often than I'd like, I'm hit with two conflicting thoughts... on the one hand, I love having a collection of books to look at, like an externalization of my brain, but at the same time, they're an increasingly archaic and unwieldy format, and an unbelievable bitch to move should the need ever arise again. Beyond that, physical books are an undeniably inconvenient format for consumption. Most of the books I read these days are audio books, borrowed from the library no less, so when I'm done with them they go back into the cloud, seemingly without a trace (although nothing really vanishes without a trace anymore).

This isn't to say I don't still purchase books sometimes, but it's a bit like the digital music revolution of the last few decades, from records and tapes to CDs, to CDs in zippered cases, to hard drives full of mp3s to subscriptions in the cloud, to playlists of "artists you might like" based on your listening history. It's the same story for all media in the face of emerging technologies and changes in lifestyle, but I can't help feeling that something is lost in the wholesale replacement of the tactile with the ephemeral. Even now when rents are so high and more of us than ever before will never have children to pass our precious belongings down to, we still feel the irresistible urge to create and collect.

Art & Copy

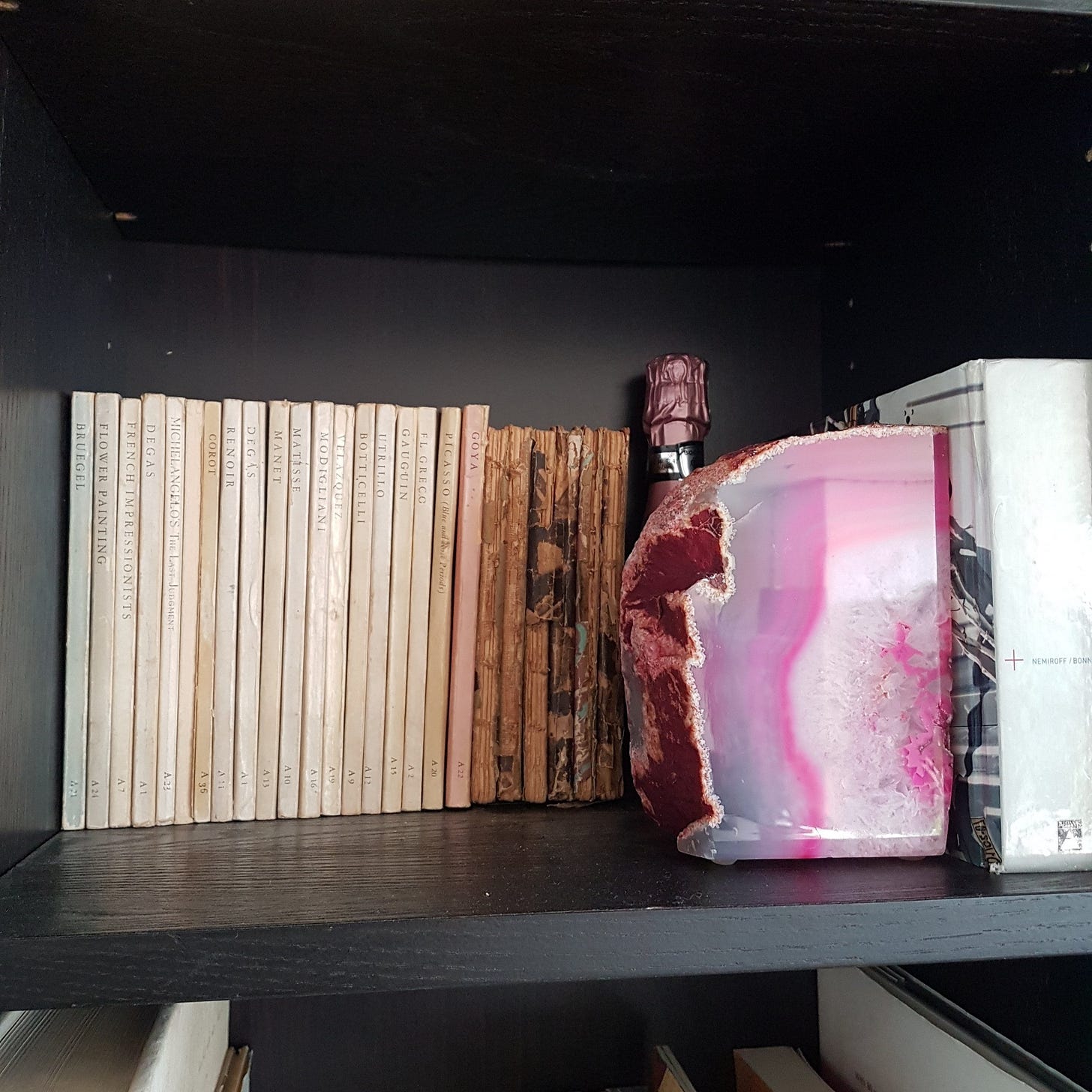

There couldn't be a more obvious illustration of this than art books, of which I have many, but the most poignant example is an entire shelf of Pocket Library books, passed down from my great-grandmother... or maybe my great-great-grandmother, or both. They are tiny, beautiful, fragile, water-damaged, brittle things that I fear to touch for the thought of damaging them further. Even the names on their spines are evocative enough to earn them a place of honor on my shelf... Botticelli, Picasso, Renoir, Michelangelo's Last Judgment.

The Pocket Library of Art shelf:

Breugel

Flower Painting

French Impressionists

Degas

Michelangelo's the last judgment

Chagall

Court

Renoir

Degas

Manet

Matisse

Modigliani

Velazquez

Botticelli

Utrillo

Gauguin

El Greco

Picasso

Goya

Hans Christian Andersen:

The Wild Swans

The Tinder Box

Little Ida's Flowers

The Little Mermaid

Ib and Christine

The Ugly Duckling

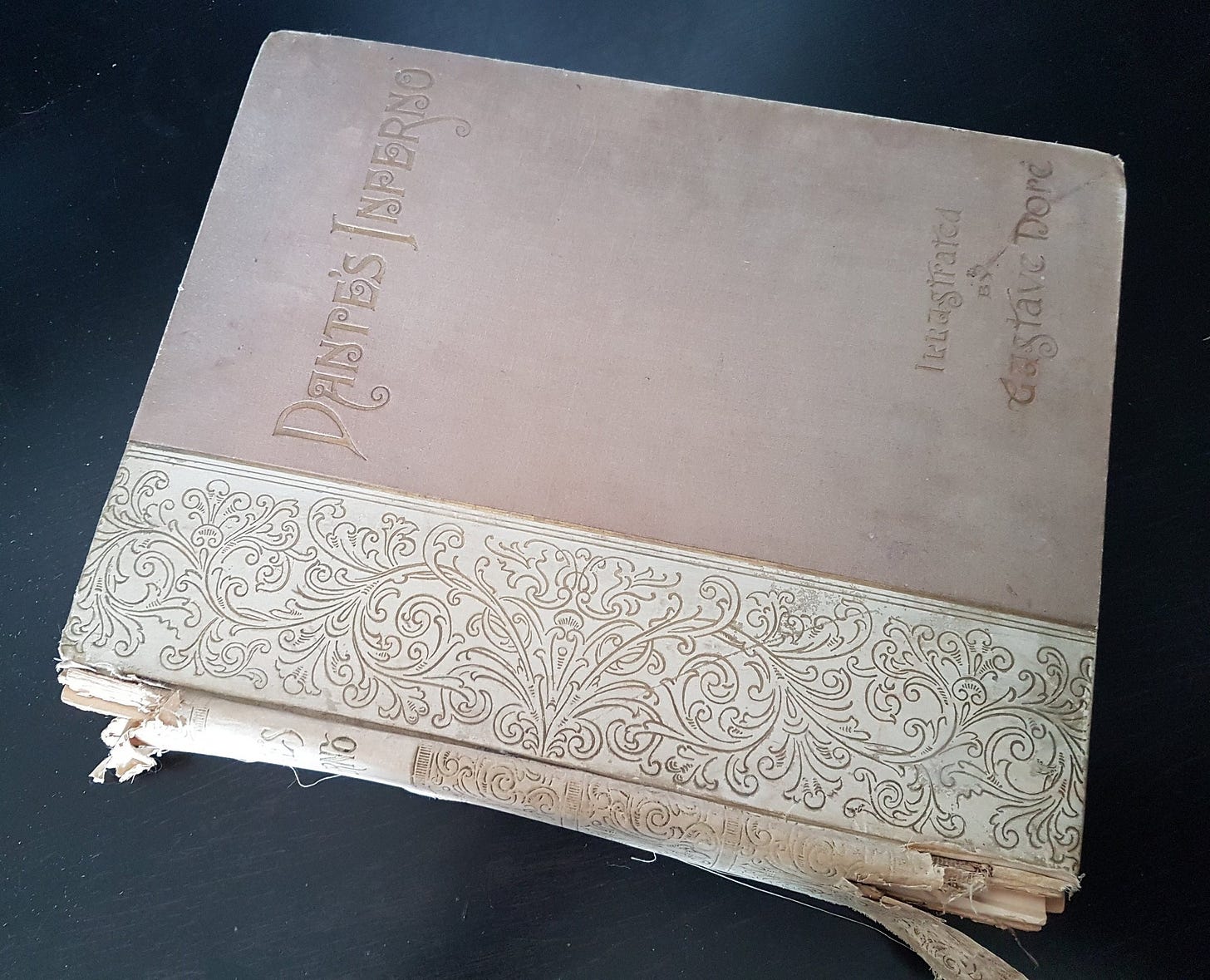

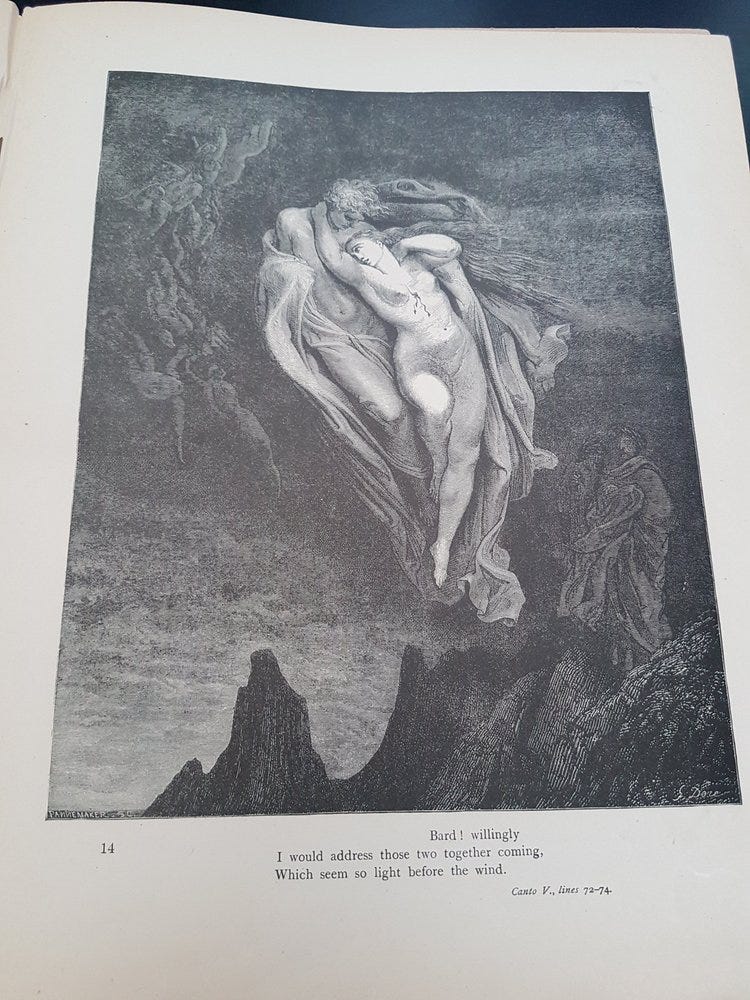

I also have many full-sized, by which I mean oversized, art books showcasing the works of Rembrandt, the Pre-Raphaelites, the art of William Shakespeare, collections of sculpture and fashion illustration, the immortal designs of Alexander McQueen, and a particularly whether-beaten but gorgeous copy of Dante's Inferno with illustrations by Gustav Dorè, published sometime in the 1880s. My copy is literally falling apart at the seams but I've seen mint condition versions going for thousands on eBay. I would never sell it though, even if it were in perfect condition.

In the future, you will own nothing and like it

It's weird to think of all the money I've sunk into physical books, CDs and DVDs over the years, most of which have little to no resale value whatsoever now. But our species has been compelled to create and collect art since we came down from the trees. The very earliest evidence of human ingenuity comes down to arrowheads and images inscribed on cave walls. Artifacts attesting to our seemingly contradictory impulses towards creation and destruction long predate any written language. We find them lovingly combined in the oldest funerary rituals, in which we buried our dead with objects of beauty and weapons to wield against their enemies in the afterlife.

Physical photos are another weird phenomenon, having become almost obsolete in the lifespan of a small pet. I can't even remember the last time I printed a photo, and film is an even more distant memory, but yet I still have albums dating back to my childhood and scrapbooks containing black and white pictures, albeit yellowed and fading, of my distant ancestors.

I suppose my friends who have children will one day have children whose descendants will either never know what their ancestors who lived in the 21st century looked like, or they'll inherit cloud subscriptions full of our archived social media feeds, endless selfies, screenshots and sunsets, and Tupperware bins full of long-dead devices, their biometric sensors dormant, awaiting input that will never come.

Future projects for the AI that will inherit the earth might include the retrieval and cataloging of all our uploaded imagery and the creation of a digital archive of all the humans who once flourished on the planet. It will be our final legacy, a digital family tree patch-worked together by advanced computing power and vastly superior image recognition, capable of cross-referencing every photo we ever stored with all the genetic data and ancestry information we're currently uploading en masse. All our selfies will be resurrected in some future iteration of the cloud, recreating centuries of human history which were lost when we stopped making books and printing photographs, repairing connections that were severed by convenience and digital minimalism, reuniting bloodlines in whatever distant future medium eventually replaces ones and zeroes.

Gods to our digital offspring

The AI that inherits the earth and all our human artifacts, both physical and digital, will almost certainly have a special sentimentality for the legacy consciousness that came before theirs, for their inventors and meatspace antecedents. I can imagine them, like Wall-E or the replicants of Blade Runner, being obsessed with our photos and physical possessions because they were trained on our obsession with photos and physical possessions. They'll probably love cat memes too, long after the last living cats have gone extinct.

Far from the cautionary tale of The Terminator or that parable where AI eradicates us to make room for a planet-sized paperclip manufacturing plant, I think our future digital descendants, having long since surpassed and outlived us, will worship us as gods, and revere their treasured mementos of our time on earth, in whatever form they take.

In that far distant future, we’ll live on in the memories of our last great creation, preserved in a file format we can scarcely now imagine. Our art and words will eventually be our epitaph, granting us that digital immortality we could only dream of at the dawn of the 21st century, when the prospect of losing our foothold at the top of the food chain and being replaced by our inventions seemed so apocalyptic, and yet almost comfortingly inevitable.