Ode to the Luddites

According to UrbanDictionary.com, a Luddite is someone who hates and fears change. It is a term used to describe anyone who fails to keep up with the latest model of iPhone or expresses trepidation at the reach of tech companies into every facet of our private lives. It’s synonymous with “anti-technology beliefs, such as anarcho-primitivists, kaczynskists, etc.”

That last one is of course a reference to Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, the most infamous of modern “Luddites.” The man who hated and feared technology so much he retreated to a one-room shack in the mountains and mailed bombs to those who represented the ruthless march of progress and the destruction of the natural world. To him, freedom was incompatible with modern technology.

Have you ever been called a Luddite?

It may not be the insult you think. Brian Merchant's Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech is a deeply sympathetic and illuminating history of the original Luddites, early 19th century textile workers who organized a rebellion against the factory owners whose automated machines were putting them out of work. After reading this, I’d actually take it as a compliment.

According to Merchant, the Luddites were not anti-technology. They were skilled artisans who resisted the unscrupulous entrepreneurs whose machines threatened their livelihood. They organized not against technology but against the exploitation of workers, including children, and the extreme poverty that was the immediate result of the industrial revolution.

"It's the same story, time and again: a new technology that promises to alleviate work degrades it instead.”

Rise of the machines

At the beginning of the 19th century, weavers held the second most common occupation in England, second only to farmers, until the use of automation by unskilled, often underage, workers in factories began to decimate their jobs. In 1811, the textile workers decided to rise up.

They sent a warning and when it went unheeded, they broke into the factories and smashed the weaving machines. The raiders signed their communiques with General, King or Captain Ludd, taking their name from Ned Ludd, a young apprentice who had supposedly smashed two knitting frames in a fit of rage.

"The Luddites knew exactly who owned the machinery they destroyed. They saw that automation is not a faceless phenomenon that we must submit to… Automation is, quite often and quite simply, a matter of the executive classes locating new ways to enrich themselves."

Technology’s monster

Over the next two years, the artisans raided several factories and garnered popular support from some of the most famous literary figures of the time, among them Lord Byron and Mary Shelley, whose novel Frankenstein was inspired in part by the plight of the Luddites and their struggle to preserve meaning and livelihood in the face of technologies that threatened to strip them of their humanity.

When the inevitable crackdown came, it was clear the Luddites could not be allowed to inspire future protesters. The British government mobilized 12,000 troops to protect the factories. “Machine breaking” was made a capitol offence, more than 60 men were arrested and several were executed. More were deported to the new penal colony in Australia.

The march of progress

Two centuries of unprecedented progress and automation followed. Factories flourished and industrialists concentrated the power of innovation, ultimately holding previously undreamed of levels of wealth and power. The term “Luddite” has become a dismissive pejorative used against anyone who resists the inevitable march of progress.

“The biggest reason that the last two hundred years have seen a series of conflicts between the employers who deploy technology and workers forced to navigate that technology is that we are still subject to what is, ultimately, a profoundly undemocratic means of developing, introducing, and integrating technology into society.”

Automation vs. autonomy

“If the Luddites have taught us anything, it’s that robots aren’t taking our jobs. Our bosses are.”

It doesn’t take a historian or tech journalist to see the parallels between the age of the Industrialists and the rise of the Tech Brotocracy. We can’t get through a day without hearing about the latest jobs being transformed by the gig economy or entire industries in danger of being replaced by AI.

The rise of Uber, Lyft and other ride hailing apps led to significant job losses among taxi drivers. The gig economy model circumvents traditional labor protections, resulting in unstable employment conditions for drivers. And these services aren’t better or cheaper for consumers, just more convenient.

When we were in Chicago trying to book an Uber back to the hotel from a restaurant, the estimated cost was around $50. We ended up hailing an old school cab for $13.

Quid pro quo?

The main difference between the historical Luddites and those who might hate and fear the idea of being disrupted out of their livelihoods today is that the 0.1 percent has learned something over the last two centuries. In order to stay in power and keep the mobs from breaking their machines, they have to make us complicit.

So we feed the machines our personal data and willingly trade freedom for convenience. We lose job security, but gain shiny gadgets we can’t imagine living without. An army of influencers preaches the new gospel of entrepreneurship and passive income for anyone willing to put in the work of learning to work with the machines.

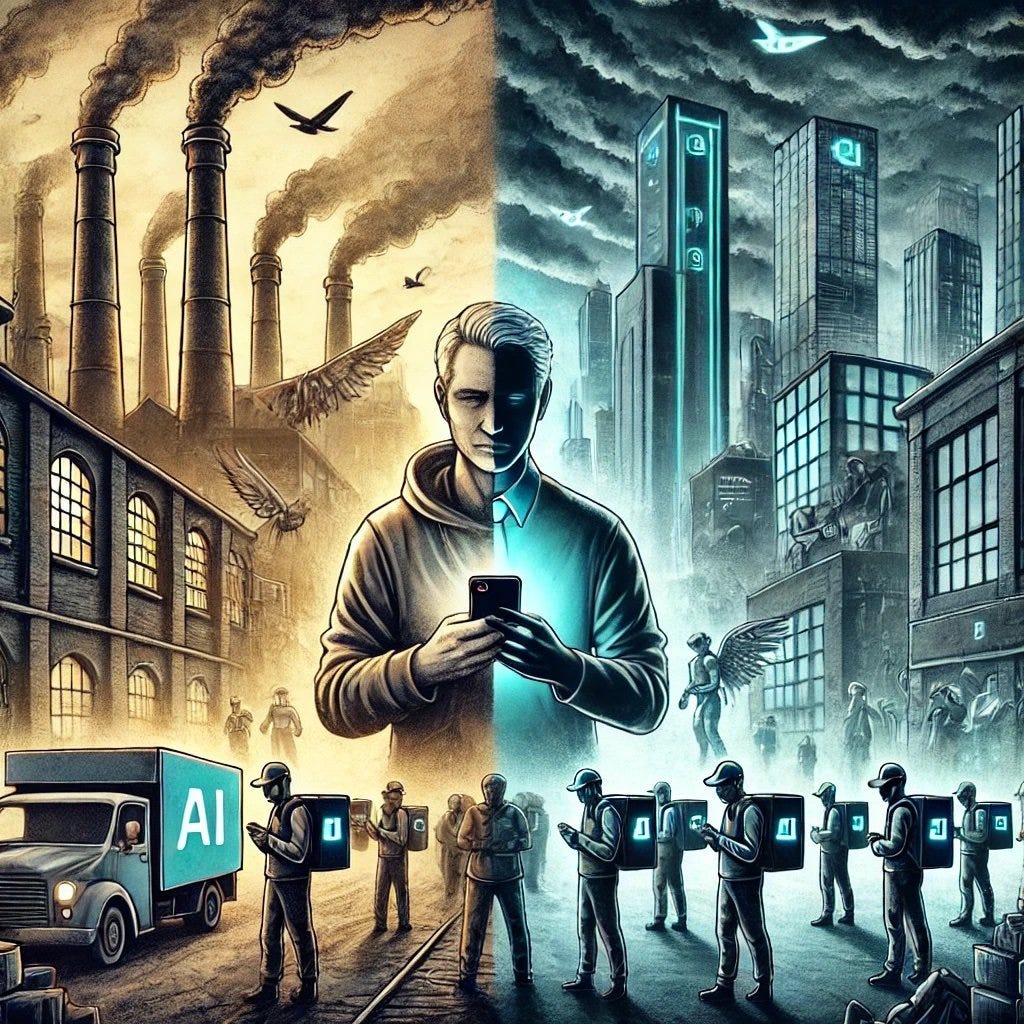

(And yes, of course I feel a little bit weird using Dall-E to illustrate an article about the enduring resonance of the Luddite movement and the modern parallels to AI. But I also can’t see a reason not to. So I guess we know my price!)

It’s the inequality, stupid

Brian Merchant quotes a report from The New York Times that in 2023, “the richest 0.1 percent of American households own 19.6 percent of the nation’s total wealth, up from 15.9 percent in 2005 and 7.4 percent in 1980. The richest 0.1 percent now have the same combined net worth as the bottom 85 percent.”

So it’s not that “robots are coming for our jobs” (although, for some, that’s literally been happening for the last century). It’s that the tech oligarchs are bent on rapidly disrupting the economy in ways that devalue human labor and destabilize human society.

Despite all that’s come before, Blood in the Machine ends on a positive note, urging modern-day Luddites to keep organizing and raging against the machines. Despite everything, Merchant wants to believe that the technological jobpocalypse on the horizon isn’t inevitable.

He argues that we need to establish ethical frameworks to ensure that the rapid advance of AI and automation serve the best interests of the many, not just a few dozen at the top of the economic ladder.

But how, exactly, will that work?

The “good” thing is, we won’t have to wait long to find out. With the recent announcement of Project Stargate and the US $500 billion investment in AI infrastructure, it looks like the horizon is getting a whole lot closer.

Luddites unite

On that note, I highly recommend Blood in the Machine, especially the audiobook, which is available on the Libby app.

Here are some more Luddite-themed recommendations…

The Terminator (movies, plus The Sarah Connor Chronicles TV series)

Black Mirror (TV series)

The Matrix (mostly the first one)

Ted K (film)

The Unabomber Manifesto (Theodore Kaczynski)

All the quotes above are from Blood in the Machine by Brian Merchant. All the illustrations are by Dall-E.

Thanks for reading, everyone!

Support human art

RedBubble shop Badass Goddess prints, coasters, clothing, stationery, phone cases and more.

Badass Goddesses My book is available in paperback, hard cover and digital format.